Christopher Austin is convinced all children are born naturalists.

“If you take a snake up to a 4-month-old, nothing happens. The babies are usually really entertained by the snake, actually,” he says. “Snakes, lizards and frogs are really accessible to kids, especially here in Louisiana.They’re in our backyards, in the ditches behind our houses. Most kids love them—until something in society eventually makes most people afraid of snakes.”

This is Austin’s answer to why he became a herpetologist. Before he was the curator of amphibians and reptiles at the LSU Museum of Natural Science, he grew up admiring tadpoles. Watching their metamorphosis into frogs felt like pure magic to him. By the time he was a teenager, he knew studying reptiles was what he wanted to do with the rest of his life.

|

|

|

Today, Austin is also the director of the LSU Museum of Natural Science. To the 10,000 visitors who come through the museum’s doors in a normal year, they know Austin’s workplace as the museum’s educational exhibits.  They think of the 1960s and ’70s dioramas of taxidermied polar bears and tigers. They picture its lifelike depictions of Central American rainforest habitats, California mountains and Louisiana landscapes.

They think of the 1960s and ’70s dioramas of taxidermied polar bears and tigers. They picture its lifelike depictions of Central American rainforest habitats, California mountains and Louisiana landscapes.

But Austin’s office is also a research museum. Past the public displays, there’s a whole other world of objects stored away. It’s full of millions of specimens of mammals, fishes, amphibians and other creatures.

Down long hallways, shelves are lined with hundreds of thousands of snakes, frogs and fishes preserved in jars of alcohol. Thousands of colorful birds are cataloged inside giant pull-out tray drawers. Each specimen is dated and tagged with its scientific name and place of origin.

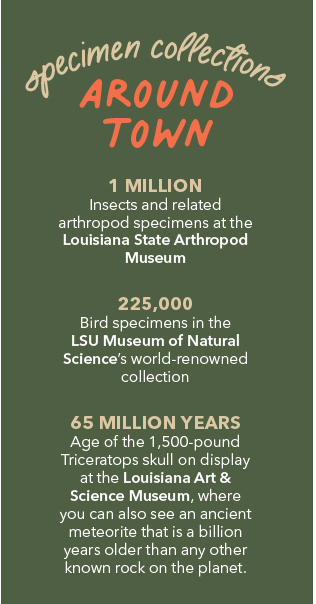

This is where you’ll find the third-largest university bird collection in the world. In terms of magnitude, it’s right up there with Harvard. The planet’s largest and oldest collection of DNA and frozen tissues is right here in Baton Rouge, and it’s an incredible resource for national and international scientists working on a variety of studies.

Students come from all over the globe just to be a part of the research happening here.

The students and professors alike all have one shared mission: to better understand the biodiversity of the planet. They go on expeditions to remote destinations across the globe. They helicopter to the tops of mountains, collect specimens, and bring them back to LSU to study.

Those specimens get loaned out to other national and international researchers working on their own studies.

They sequence genomes. They study regional and global evolution patterns.

And they encounter previously undiscovered creatures. The museum has been responsible for the discovery of 134 new species—and counting.

“We do not know how many species there are on the planet. We just don’t,” Austin says. “There are estimates, but they vary wildly.”

The museum’s collection dates back to 1936. And as long as today’s specimens are well preserved, they will continue to be incredibly valuable, because they will be studied for hundreds more years.

It’s why Austin is always thinking 500 years into the future. He knows his biology research will long outlive all of us—and our kids, grandkids and grandkids’ kids.

“We are doing things with specimens today that I had no idea we would ever be able to do 30 years ago when I was a graduate student. Who knows what we’ll be able to do with them in 100 years,” he says. “The specimens we are collecting now will be used by generations down the line. The LSU Museum of Natural Science is a library for biodiversity.” lsu.edu/mns

Christopher Austin talks three topics he and his colleagues are studying at the LSU Museum of Natural Science

Christopher Austin talks three topics he and his colleagues are studying at the LSU Museum of Natural Science

As told to Jennifer Tormo

The New Guinea puzzle

“A lot of my research focus is on the island of New Guinea. It’s the largest, tallest tropical island in the world, just north of Australia. And it’s a biodiversity hotspot. It’s less than 1% of the world’s land area, but it’s predicted to have 5-7% of the world’s biodiversity. Its main mountain range is about 5 million years old, and from a biology and geology standpoint, that’s super, super young. And yet, it has a ton of biodiversity. As opposed to a place like the Amazon, which also has lots of biodiversity but has been very, very geologically consistent over the course of more than 55 million years. So it’s sort of a conundrum about why there’s so much biodiversity on this island.”

The green-blooded lizard

“There are lizards from New Guinea that have green blood. Their bones are green, their muscles are green, their heart is green, and their tongue is green. The lining of their mouth is green, as well.

So, what the heck is going on with these lizards?

They have so much green pigment in their blood it overshadows the crimson-red color. It’s a biopigment called biliverdin that causes jaundice in all vertebrates.

You have biliverdin in your blood right now, but not very much. Your liver is like the oil filter of your car, and if you’re healthy, it is filtering those biopigments out.

But these lizards have concentrations of biopigments in their blood, that if you or if I had them, we would be dead.

One of the things my lab is working on is piecing together the story of these green-blooded lizards and trying to understand why they aren’t dead.”

The world’s smallest vertebrate

“In 2009, I did an expedition to the south coast of New Guinea, and we collected a new species of frog. It turned out to be the smallest vertebrate in the world. Adults are 7.7 millimeters in length, on average. That’s really, really tiny.

What’s cool about these frogs is that they don’t sound like frogs. They sound like insects, and that’s why the species had gone undetected for 100-plus years. When herpetologists walked in the forests at night, they heard these things and thought they were crickets or insects, not frogs.

All amphibians are highly susceptible to water loss. And when they’re as tiny as these micro-frogs, they would dry up if you put them in the sun.

|

|

|

Up until our 2012 publication about these frogs, the smallest known vertebrate in the world was a fish. Of course, fish live in water, and they don’t have to worry about drying out.

And so it’s really interesting that these frogs have evolved into a habitat that presumably has been stable enough, from a water perspective, that they can survive there.”

This article was originally published in the June 2021 issue of 225 magazine.