Aerial file photo of downtown Baton Rouge

Over the weekend, a story in The Advocate about how downtown Baton Rouge struggles to embrace the river prompted Mayor Kip Holden to get on the defensive. He held a press conference Monday to remind everyone of all the major downtown improvements in recent years.

He missed the point, though. No one was overlooking how far downtown has come—with the Shaw Center, improvements to the River Center, North Boulevard Town Square, Galvez Plaza, the resurgence of Third Street, several popular downtown festivals, a full-service grocery store and the sparkling new IBM offices, among other things.

The Advocate story was instead about the riverfront downtown and elsewhere in the parish. All of those great improvements happened across the levee, away from the Mississippi. The truth is: we’re a riverfront city with not much focus on the river.

I wrote about this topic back in 2013 when the first renderings of the IBM development were released. It was a pretty illustration of a gorgeous modern building. But it was depicted facing some railroad tracks and a slope of gravel down to a muddy river bank:

Now that it’s nearly finished, it still has the same sad view. Granted, the designers could only use the landscape currently available to them when creating the rendering, but it was a stark reminder of how little we pay attention to the riverfront.

Earlier this summer, the threat of a new barge-cleaning facility along the river near a major BREC park prompted the Metro Council to look—as if for the first time ever—at how property along the Mississippi is actually zoned. Not surprisingly, they found it is mostly zoned for industrial use, including the riverfront downtown. And not just any old industrial use, but the heavy, polluting kind along the lines of ExxonMobil just north of the capitol.

Clearly, few people in our city government’s history ever considered the potential quality of life uses for the riverfront, but instead focused on it solely as an access point for big industry.

As I said in the 2013 post, the way we design our city and its major landmarks speaks volumes about how urban design plays a huge part in linking—or not linking—people to the surrounding landscape.

Take a look at the Louisiana Art & Science Museum. It’s a stately building if viewed from River Road, and the Downtown Development District has continued to improve and landscape its entrance area. But from the levee, it’s mostly a brick wall up against railroad tracks. Only a few windows in upstairs galleries remind you that you are in fact facing the riverfront.

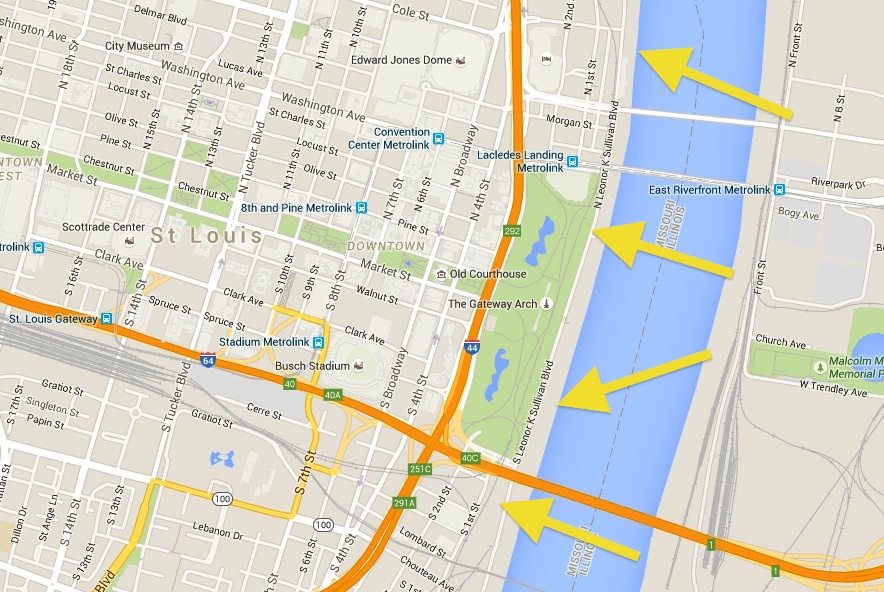

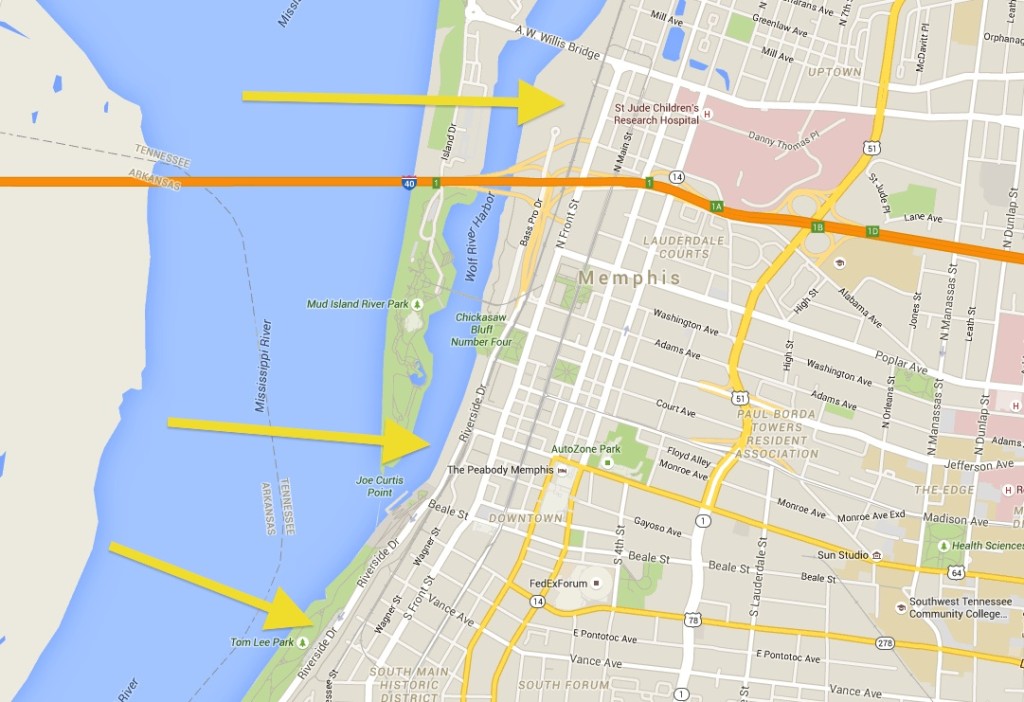

Holden and other officials have argued that the biggest obstacles in the way of true riverfront development are the levee, managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, and the railroad, managed by Canadian National Railway. They point to other river cities, like St. Louis, Memphis or Chattanooga, that have been more successful developing their riverfronts because they aren’t impeded by levees and railways.

Except that’s only true for one of the cities they cite. St. Louis has floodgates along most of its riverfront, and a railroad, too. But the city built up a park for the iconic Gateway Arch and the railroad tunnels directly underneath it. Memphis also has a railroad and floodgates standing in the way of its riverfront access, but they found a way around it to develop several small parks and pathways along the river.

St. Louis, with yellow arrows pointing to the railway:

Memphis, also with arrows pointing to the railway:

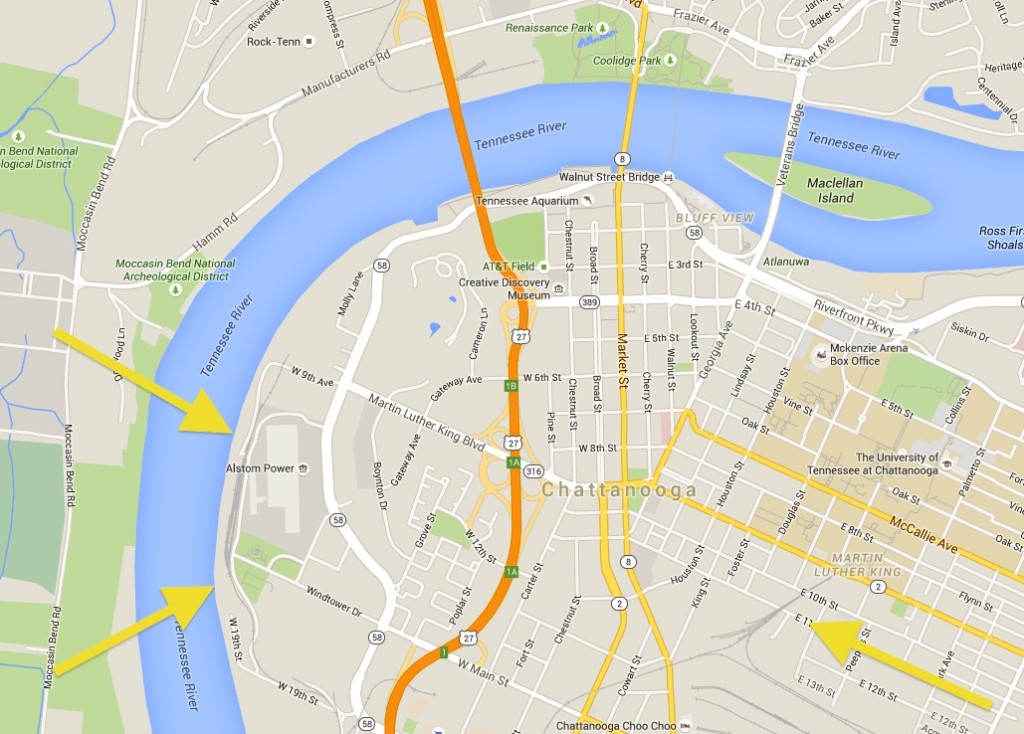

Chattanooga is the only one that doesn’t face those problems, but that’s due more to the hilly terrain along the Tennessee River than anything else.

Chattanooga, with yellow arrows showing railways on the outer edges of the downtown riverfront:

If anything, those example cities show there are ways around the obstacles that we say prevent us from truly utilizing our riverfront. Let’s keep in mind, New Orleans also has a levee and railroad along its riverfront, and it’s doing just fine creating beautiful new urban spaces.

Fortunately, downtown has slowly started to remember its greatest asset. There’s a brand new riverfront access on Florida Street that includes a ramp for people with disabilities. Just two years ago, that entrance was an awkward set of stairs made out of rotting railroad ties. Officials are planning a competition for a massive sculpture that will sit on an overlook at the Florida Street access, surely to draw more visitors.

Of course, the Florida Street riverfront access and the lengthy process of getting it built is indicative of how much we are at the mercy of the people who own the levee and the railroad. In a Facebook post about the opening of the new riverfront access, Downtown Development noted the new tables and chairs set up on the platform. Someone asked why there aren’t any shade trees around the seating areas. The response was simply that the Army Corps of Engineers “will not allow trees.”

In any case, more improvements and beautifications are slated along River Road that will extend to the IBM offices and make it more pedestrian friendly.

There was also the unveiling earlier this week of the rendering for the Water Institute of the Gulf’s headquarters, which will rise up from the old city docks just south of the Mississippi River Bridge. Besides our three major casinos on the river, this will be the first huge development in Baton Rouge in a long time that actually puts visitors over the water (and doesn’t have an age requirement to get in).

Let’s hope this is one of many new steps toward finally embracing the Mississippi River in Baton Rouge. Because while big developers are slow to test the waters, locals are already jumping in.

Smart City is an occasional blog about smart growth in Baton Rouge. Contact the writer, Benjamin Leger, at benjamin@225batonrouge.com.