Where will Capital Region residents most likely live in the future? We look at two important factors: suburban flight and millennials

ROCKIN’ THE FLOOD-PRONE SUBURBS

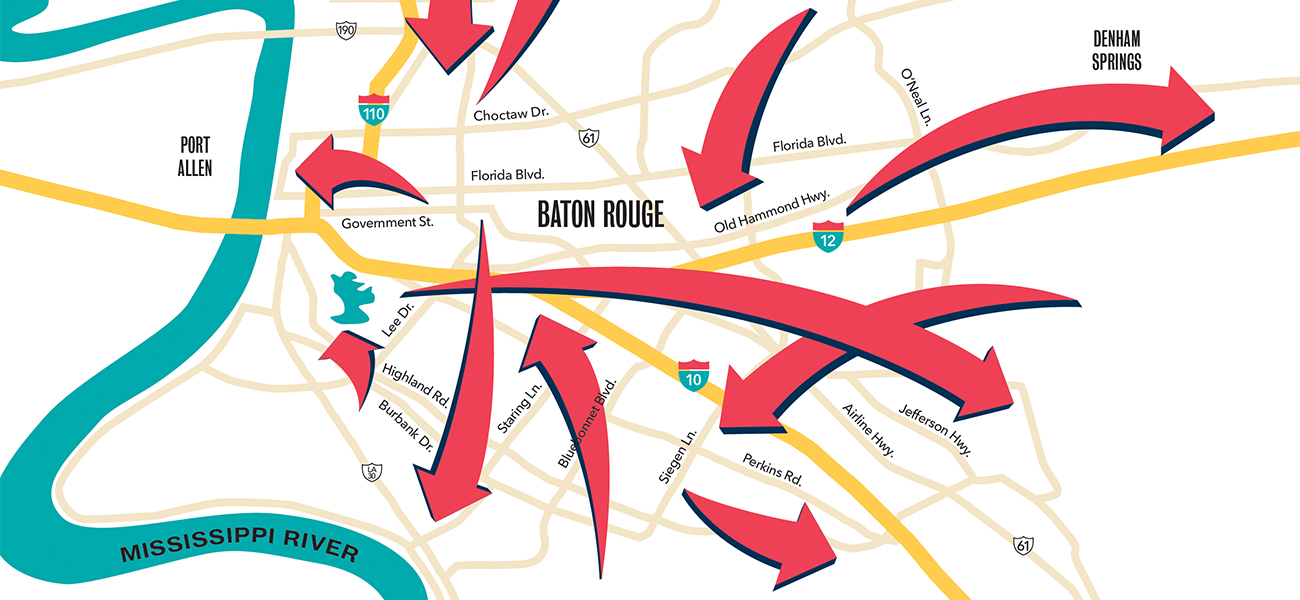

Trends come and go, and in 2019, Baton Rouge residents are trending back out into the suburbs—much as Americans did in the 1950s. Census figures from 2017 show Baton Rouge’s population dropped by 7,700 since 2010. Meanwhile, Ascension and Livingston parishes are considered the fastest- and third-fastest-growing parishes in the state, respectively.

What does that mean for the Baton Rouge of the future? It’s difficult to predict, and the ramifications of the 2016 floods appear to be what’s kept things in flux.

|

|

Michael Barton, associate professor of sociology at LSU, has studied neighborhood changes in Baton Rouge and New Orleans. “There was a lot of growth and development going on in the suburbs, and then those areas flooded. Things started to slow down and people started to question if our flood maps are up to date,” he says. “But the further we get away from it, people start to say, ‘Well, maybe it’s just a 500-year thing.’”

Even if our memories are short, the federal government’s National Climate Assessment confirms extreme weather events will only increase. The 2018 report says rural areas with outdated infrastructure and crumbling bridges are the most vulnerable to floods.

But the 2016 catastrophe hasn’t stopped developers from setting their sights across the Comite River in Livingston Parish or in the sprawl surrounding Prairieville and Gonzales.

Barton says these mostly unincorporated areas provide developers more freedom to build how they want with little oversight. But that’s also led longtime residents to push for a cap on new construction or stronger flood prevention restrictions.

Many of these new developments cater to higher income brackets, and Barton points to recent floods in Houston that prove more affluent neighborhoods aren’t immune to bad weather.

“These middle-class and upper-class households will start to realize that they are not as protected as they thought, and people become more cognizant of this potential for flooding,” he says.

And with another 100-year flood more likely to be seen in a few years rather than decades, the chances of a housing scramble and subsequent population shift are as high as those record water levels.

WE BUILT THIS CITY ON MILLENNIALS

We all know the jokes: Millennials love avocado toast, they’re addicted to cold brew, and they hate straws. They are also more inclined to live close to the city center, where they can bike or walk to work or to the nearest coffee shop for that toast and strawless coffee.

According to Downtown Development District, 20- to 34-year-olds make up the largest demographic of residents downtown at 33%. The rest of them seem to be buying or renting bungalows in Mid City and the Garden District—two areas that have seen an explosion of hip new hangouts.

Economists have started referring to millennials as “the lost generation” because many of them entered the workforce during the Great Recession, giving them a disadvantage on top of crippling student debt. They recently surpassed Baby Boomers as the largest adult generation, yet they face lower wages and higher living costs, according to Pew Research Center.

Some research suggests millennials across the country will slowly flee to the suburbs for cheaper homes and bigger square footage for growing families—potentially adding to the already exponential growth outside Baton Rouge.

Other research points to an increased investment in city centers. Millennials are more diverse than other generations, and diversity thrives in urban areas. Millennials are also becoming more engaged civically, and once they’ve gotten a taste for urban renewal, they may be inclined to stick around and put in the work to continue revitalization.

But the rising cost of housing in sought-after areas like Mid City might still push some millennials out if they didn’t get into a home before the 2016 floods jacked up the prices.

Where to, though? Signs point to staying as close as possible to the city center without leaving the parish.

The established Broadmoor neighborhood has become a spot for young professionals, as Heather Kirkpatrick, an agent with eXp Realty, told Business Report in December 2018. “They love Mid City, but for what they would pay for a home in Mid City, they’re only getting around 1,200 square feet. In Broadmoor, you’re getting more square footage [for that same price]—more bang for your buck.”

Other neighborhoods like Kenilworth and Tara are destined to see similar trends. Meanwhile, the Government Street redesign will inevitably push young professionals over to the north side of the trendy corridor for less expensive homes between Government Street and Florida Boulevard—similar to what occured in Ogden Park in recent years.

Millennials will likely accumulate less wealth than their parents did, according to a bleak 2018 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Meaning: Even if they do move to the suburbs, it probably won’t be for a McMansion in a fancy new neighborhood development.

This article was originally published in the November 2019 issue of 225 Magazine.

Click here to see more stories from our Imagining the Future cover story.

|

|

|