From the archives: Boarding house ledger tells BR black history

Kevan Cullins with the ledger that gives clues to Baton Rouge’s black history. Photos by Lori Waselchuk

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in the November 2006 issue of 225.

By Alex V. Cook

Not just anyone stayed at Miss Sing’s house, just the ones who really didn’t have much choice.

|

|

Miss Sing operated a boarding house in the 1940s and ’50s on Oleander Street in the Garden District. And hers wasn’t the only local Jim Crow-era boarding house for black travelers, says Kevan Cullins, a blues musician and electrical contractor.

Cullins’ grandmother operated a boarding house for bricklayers and other laborers. But his grandmother’s best friend, Leona Stewart Pearson—affectionately known as Miss Sing—hosted some of the most important and influential African-Americans of her generation.

And Cullins, 48, possesses the hefty guest book to prove it.

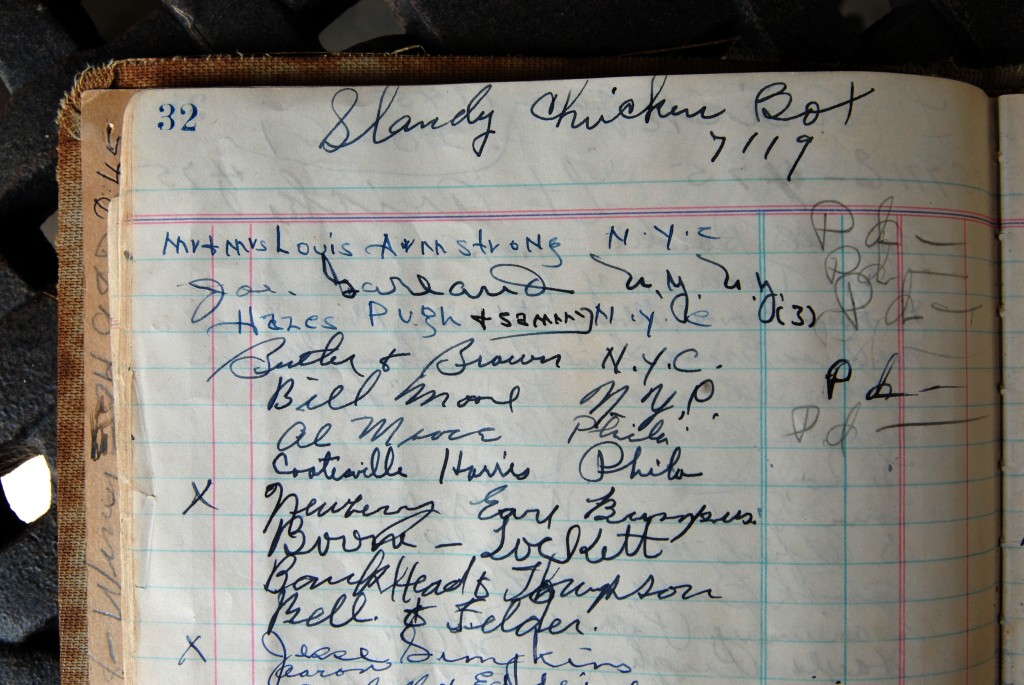

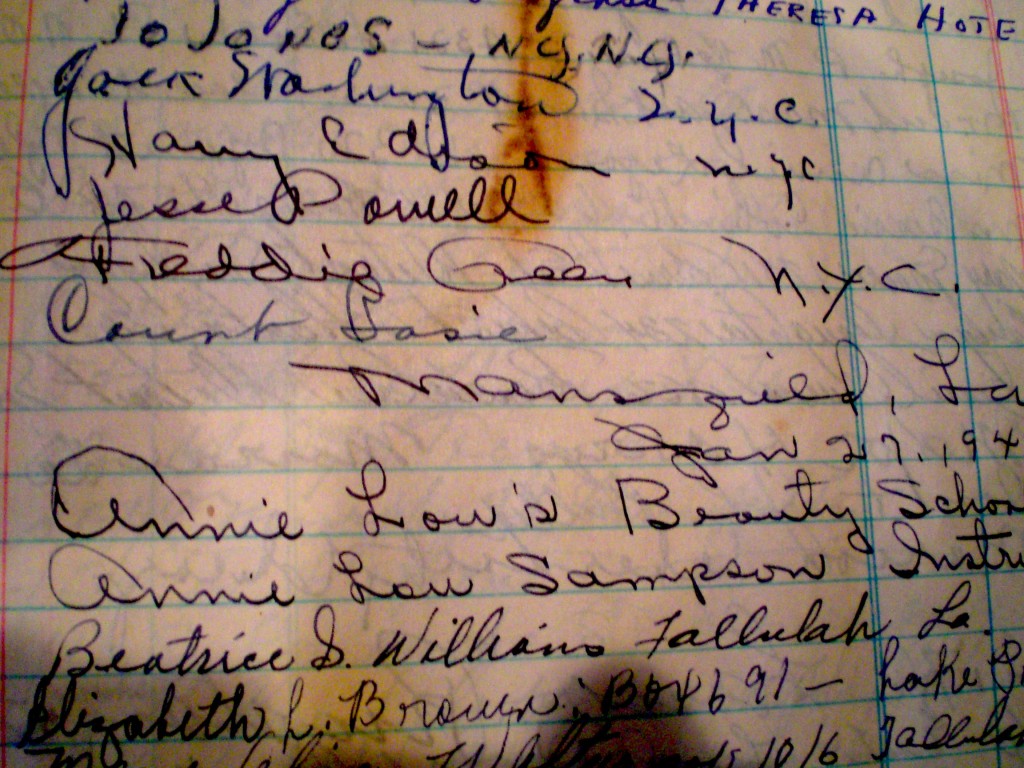

Like a relic of American history, it contains page after page of entries by weary black travelers who stayed the night in Baton Rouge. Musicians, politicians and preachers fill its yellowing pages. Among the many signatures are some of modern black history’s most important names: Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Thurgood Marshall. A young guitarist named Riley King’s signature is in the book. Cullins met the musician later in life and asked him to re-sign it with his more famous stage name—B.B. King.

“Miss Sing’s place was a high-class establishment, not some old flop house like where these guys sometimes had to stay,” says Cullins. “Miss Sing once told me that Louis Armstrong always liked her red beans, and she would fix a jar of it for him to take on the train with him out of town. Last time he stayed there, he took one of her silver spoons to eat them with.”

Black-friendly places like Miss Sing’s on Oleander once were listed in The Negro Motorist’s Green Book, a guide for friendly shops and accommodations for African-Americans, published by Victor Green. The book’s purpose, Green wrote, was to save black travelers “as many difficulties and embarrassments as possible.” Tucked in the front of Miss Sing’s old ledger is a letter from Green asking Pearson if she would like to advertise in the book.

Miss Sing’s boarding house thrived in the 1940s and ’50s. But by the ’60s, motel chains like Howard Johnson’s started opening their doors to black travelers. This slowly—and thankfully—made the Green Book and places like Miss Sing’s obsolete.

Cullins came to possess the ledger as a gift for an act of kindness.

In the early 1990s Miss Sing asked Cullins to repair the electric motor in her doorbell chimes. “It was one of those multiple chimes that hangs down with four chime rods. Not the electronic crap today,” Cullins says. “It was a musical instrument.”

Cullins refused to accept payment for the repair. “She said, ‘Come here, baby. I know you’ll like this,’ and opened the door to the telephone table and handed me an old book.”

The names on the pages stunned him, and he figured it carried historic, even monetary value. A visit to Dillard University in New Orleans confirmed that when a professor he asked to examine it blurted, “What are you doing with this thing out in public?”

Today Cullins stores the ledger in a fireproof safe. He says he’d consider selling it to the right buyer, but he’s not made any formal inquiries to museums or universities that might be interested in its historic value.

Miss Sing died in 1996, but thanks to the ledger—and Cullins’ appreciation for what it contained and represented—her legacy lives on.

|

|

|