Marvin Taylor was sitting in a Baton Rouge barbershop skimming newspaper headlines when a story about kids needing help caught his attention.

“I saw that it said they needed men,” says Taylor, 35. “I’m a man. So I kept reading. Then I saw they needed African-American men, which I am, so I kept reading.”

By the time he finished the story about the local CASA, the Capital Area Court Appointed Special Advocates for Children Association, he knew he wanted to volunteer.

CASA helps abused and neglected children by matching each one with a trained volunteer who serves as a proverbial bridge between them and the legal system.

“A lot of these kids lack a male role model in their lives. They need a strong advocate with a strong voice.”

—Jennifer Mayer, recruitment coordinator for the local CASA

Abused and neglected are broad terms to describe the children who find themselves wards of the state. In some cases, their parents are imprisoned; others are addicted to drugs and alcohol and not capable of taking care of themselves or their children. These children are often shuffled between different foster homes, schools and group homes and lack a sense of security and consistency.

“I come from a home with two parents and three brothers and realized how lucky I was,” says Taylor, who has now been a volunteer with CASA for five years. “There were kids out there who did not have anyone. And here I was reading a story that said they needed someone like me.”

Taylor currently works with two boys, ages 9 and 15. The 15-year-old has not seen his parents in five years.

While CASA volunteers sometimes accompany a child in the courtroom, most interactions occur outside of court. Taylor has brought the children to doctor appointments and met with their social workers, teachers and foster parents. There have also been fun outings, too, such as playing laser tag and riding go-carts. His role is to understand the needs of the children he works with and help the court find a permanent home for them.

“There are lots of kids who come through that system with shattered backgrounds,” says Taylor, a regional manager for a building maintenance company. “As a CASA, we get a chance to find out what they need.”

CASA officials say they need more men like Taylor.

For the past year, Jennifer Mayer, recruitment coordinator for the local CASA, has led a marketing campaign called “Be the Man” in an effort to recruit more men—and specifically more African-American men—to volunteer for CASA.

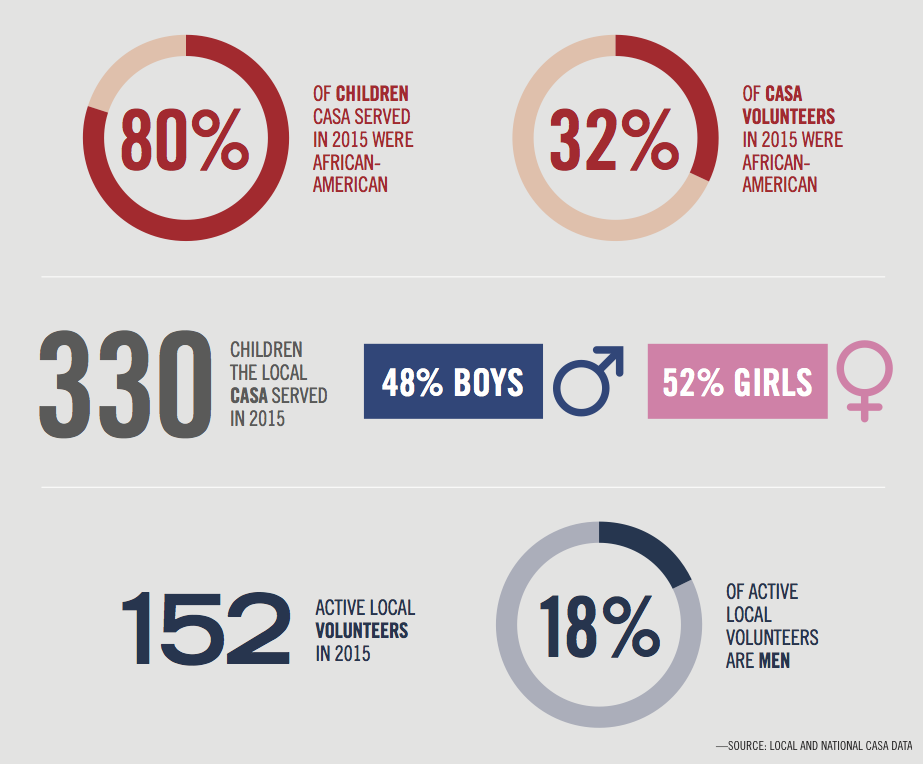

Mayer says statistics show nearly 80% of the children served in 2015 were African-American, but only about one-third of CASA volunteers were African-American.

“I come from a home with two parents and three brothers and realized how lucky I was. There were kids out there who did not have anyone.”

—Marvin Taylor, local CASA volunteer

While the local CASA serves about an equal number of male and female children, Mayer says there are more women volunteering to advocate for them than men. Only 18% of volunteers in 2015 were men. That number is on par with national CASA statistics, where 82% of all volunteers are women.

“A lot of these kids lack a male role model in their lives,” Mayer says. “They need a strong advocate with a strong voice.”

To find more men, Mayer stepped up the advertising for her campaign in newspapers and talked about CASA in news broadcasts and radio spots.

Brent St. Blanc, a mechanical engineer, heard a radio ad while driving home from work one day and decided to volunteer.

“Listening to someone describe this job was overwhelming at first,” says St. Blanc, 57, who has been volunteering for three years. “I was not familiar with the juvenile judicial process, but for me the epiphany to get involved was that I could either say, ‘Hey, that’s horrible,’ and look away, or I could run to it. And I ran toward it.”

St. Blanc works with a 13-year-old boy whose parents just got out of prison. The boy lives in a group home but wants to be reunited with his parents. For St. Blanc, working with the child has been a humbling experience.

“What I would expect for my kids isn’t always the same as what other parents expect for their kids, and I had to learn to lower my expectations,” St. Blanc says. “The desire for these kids to be with their biological parents is high.”

Baton Rouge Juvenile Court Judge Pamela Taylor Johnson recognizes the importance of the program. She appoints CASA volunteers at the beginning of a case to help assist and gather information for her.

“They’re the voice of the child for us,” she says. “They are the eyes and ears, and they see the child more frequently than me. I’m only going to see that child maybe three times per year.”

Craig Winchell has been volunteering with CASA for two years. The 58-year-old father and grandfather is an academic advisor for student support services at LSU with a history of coaching, teaching and helping those in need. He decided to get involved in CASA after he saw two different advertisements in the same weekend—in the paper and at church. He works with a 15-year-old boy who was living on the streets last year. He slowly established trust with the teenager through consistency, perseverance and reliability.

Craig Winchell has been volunteering with CASA for two years. The 58-year-old father and grandfather is an academic advisor for student support services at LSU with a history of coaching, teaching and helping those in need. He decided to get involved in CASA after he saw two different advertisements in the same weekend—in the paper and at church. He works with a 15-year-old boy who was living on the streets last year. He slowly established trust with the teenager through consistency, perseverance and reliability.

For the boy’s birthday, Winchell planned on taking him out to a nice restaurant, but plans changed when the boy told Winchell all he wanted was a couple of chicken sandwiches from a fast food restaurant.

Winchell has learned that it’s the little things that feel like big things to a child who doesn’t have much, like the homemade chocolate chip cookies he brings when he visits or the respect of answering or promptly returning the child’s phone calls. Being a constant adult figure in the boy’s life is more important than a fancy meal.

“I find that if I make a commitment to see him, come hell or high water, I better see him,” Winchell says. “He knows I’m there for him, and I’m able to be a stable person in his life.”

Taylor, who is now the father of two small children, says being a dad has brought more meaning to his volunteerism.

“Having kids made me understand why we do what we do,” he says.

CASA’S ORIGINS

A juvenile court judge in Seattle, Washington, started CASA in 1977 in an effort to recruit volunteers to help make the best choices for abused and neglected children shuffled through the court system.

CASA serves children from birth to 18 years old and pairs them with volunteers who commit to helping the child for at least one year. Their time with the child ends when “permanence” is achieved—either the case is closed, a child is reunited with a parent or parents, adoption occurs, or the child turns 18 and is no longer the responsibility of the state.

Many court systems are overwhelmed with juvenile cases, so the Seattle nonprofit grew and is now found in 49 states and in Washington, D.C. The Baton Rouge CASA was started in 1992 and has served more than 2,200 children since inception. casabr.org