“Every morning in Africa a gazelle wakes up. This gazelle knows it must run faster than the fastest lion, or it will be killed.

“Every morning a lion wakes up. It knows it must run faster than the slowest gazelle, or it will starve to death.

“Now, gentlemen, it doesn’t matter whether you are a lion or a gazelle. The moral of the story is this: When the sun comes up, you better be running.”

When I first heard this story, I was 14 and scrawny and more than a little intimidated by the coach shouting it at the pimpled faces of hundreds of basketball players—many older than I was—at Dixie Basketball Camp (and Country Club, hey!) in Summit, Miss.

It was a no-brainer for me. I identified with the gazelles.

At the time, it did not occur to me that any significant meaning could be derived from this parable other than the direct correlation between being fast and surviving a sub-Saharan big cat attack.

Now, I see that it applies to all walks of life, and that, just maybe, we are best served by the ability to shift from lion to gazelle and vice versa, to see our value not in terms of our own being, of our own lion-ness or our own gazelle-ness, but in our doing—doing good for others.

Sonja Lyubomirsky is a professor of psychology at the University of California-Riverside. Her new book The Myths of Happiness: What Should Make You Happy But Doesn’t makes a cogent argument for seeking happiness, not as an end unto itself, but instead encountering it as a byproduct of serving family and community to the best of our abilities.

Instead, modern Western society tells us to invest large quantities of time and effort into our careers, which can be positive, but when escalated to the point that we build our identities on our work as a measurement of purpose and survival, the disappointment and stress can be crippling.

“In one hour’s time, I will be out there again,” says English Olympic sprinter Harold Abrahams in the Academy Award-winning film Chariots of Fire. “I will raise my eyes and look down that corridor…10 lonely seconds to justify my existence. But will I?”

Abrahams is looking to justify his existence by his performance on the track. As such, he is afraid of losing and of winning, fearful that the thrill of first place will fade too fast, leaving him bitter at himself for having heaped so much hope and the responsibility of his personal happiness onto a medal.

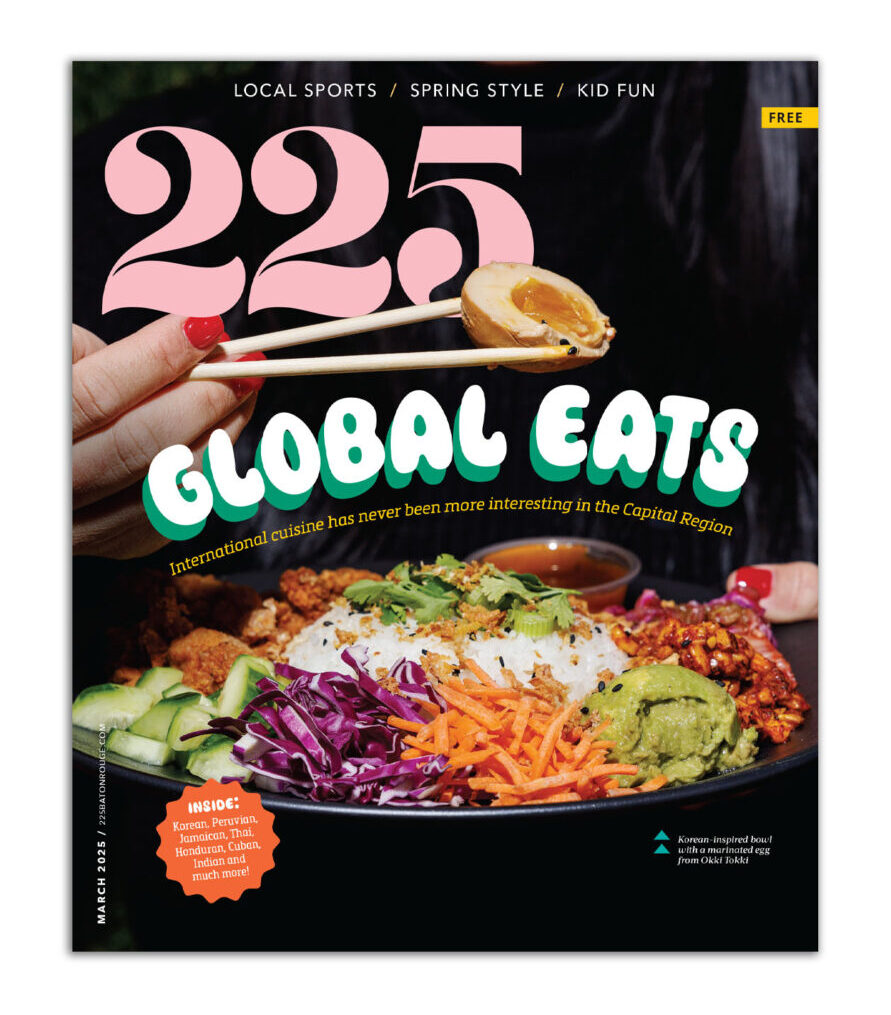

World champion hurdler Lolo Jones has not earned an Olympic medal, and yet, she may still, either with the USA bobsled team or—stranger things have happened—hurdling at the 2016 games in Rio at the age of 34. But already the former LSU Tiger is adapting.

This month’s cover subject has launched The Lolo Jones Foundation in Baton Rouge to aid families and children with loved ones that are incarcerated.

Through this achievement, Jones will get a different kind of medal, one draped around her neck by the gratitude of those whose lives she helps to improve or, just maybe, even save.

It may not be as shiny, or come with as much applause, but it sure makes for a good run—every morning, when the gazelle wakes up.