When she cleans, Brittany Jones thinks of her uncle.

Darrel Guy died on a Tuesday. He had been sick all weekend, sweating and burning up with a fever. On the last day of his life, he was rushed to the emergency room and diagnosed with COVID-19. Within a few hours, his heart stopped beating.

That September day, Guy—a pastor, husband, father and uncle—was added to the pandemic’s death toll.

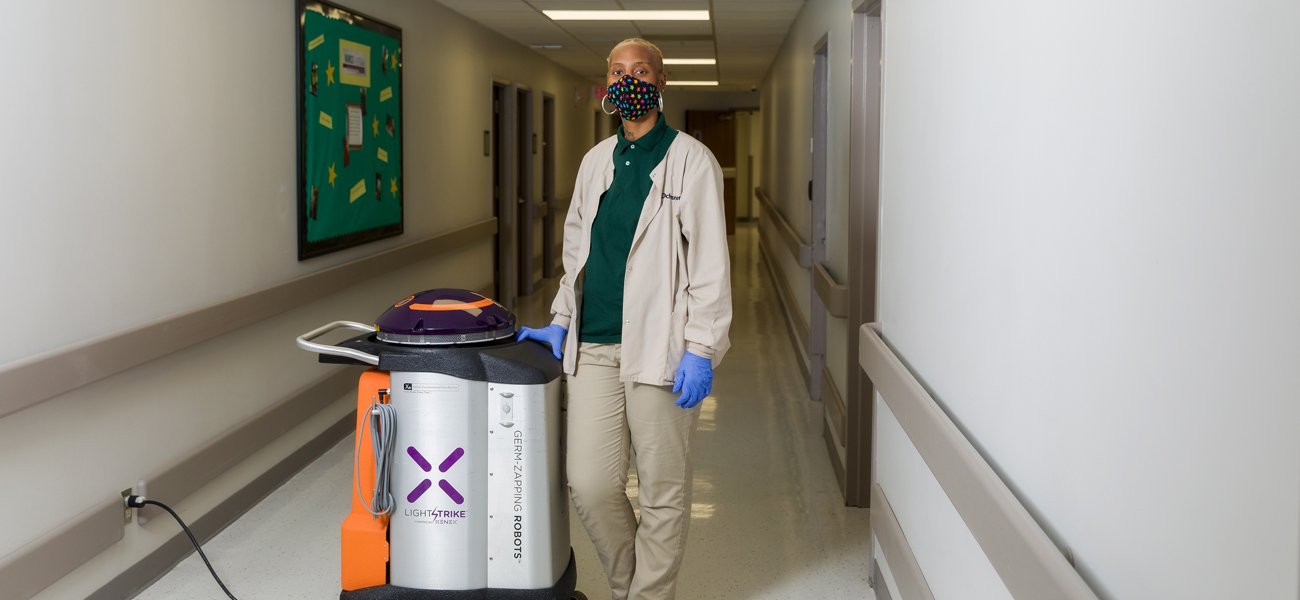

It’s his face Jones sees as she scrubs the walls of the COVID-19 unit at Ochsner Medical Center. It’s his voice she hears as she disinfects each room’s curtains, mattresses and medical equipment. She pictures her aunt and two cousins, who each faced their own three-week battles with the virus after Guy’s death.

Jones misses her uncle every day. “More than anything,” she says.

It’s a cool October morning, one month since her uncle died, and Jones speaks wistfully about what could have been—should have been. Guy was supposed to bless her new house this year. Now, he’ll never get that chance.

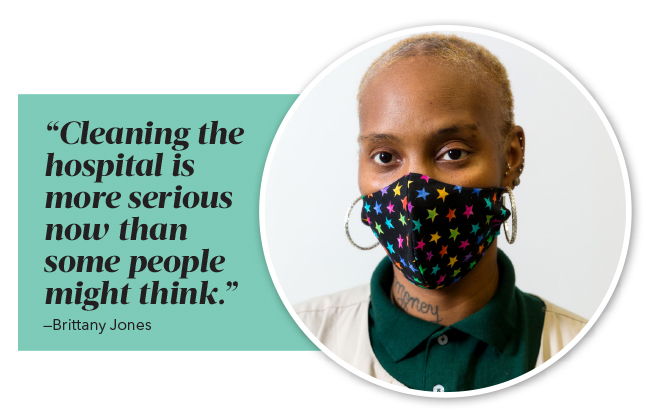

Long before the pandemic affected Jones’ life personally, she’d been working in hospitals. She’s been an environmental services technician at Ochsner for two years. She says she’s always loved to clean. And when a family member who works at the hospital sent her the application, she “jumped right on it.” Jones enjoys interacting with the patients and her coworkers, and even volunteers to work extra on the weekends when she’s off.

In normal times, she’d clean the patient rooms, waiting rooms and hallways; polish windows; and pick up trash outside the hospital.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak reached Baton Rouge, though, her job has been more critical than ever. She arrives to work at 6 a.m. each day to begin her cleaning rounds.

She and her coworkers wear heavy PPE to protect themselves. When they enter a room that has been occupied by a COVID-19 patient, they put on a mix of protective scrubs and gowns, gloves, goggles and/or face shields, surgical hats and N95 masks. Cleaning while wearing the equipment is grueling. It’s hot and hard to breathe in. But Jones doesn’t complain.

She and her coworkers are also armed with Virex 256 surface cleaner; disinfectant misting sprayers that disperse chemicals; and Xenex, a germ-zapping robot on wheels that’s about half Jones’ height.

Since the pandemic began, Ochsner’s use of Xenex robots has increased by more than 70%, and the use of disinfectants has jumped by approximately one-third. The environmental services team dedicates more than 2,200 hours per week to keep the hospital clean.

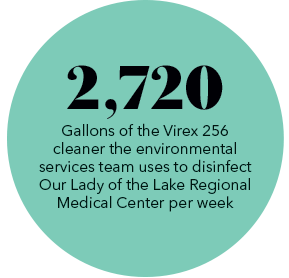

Over at Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center, the 222-person environmental services team also cleans and sanitizes the facility 24 hours a day, seven days a week. They clean more than 15,000 patient  rooms monthly, not to mention all the waiting areas, bathrooms and operating rooms. The cleaning and re-cleaning amounts to more than 2 million square feet per day.

rooms monthly, not to mention all the waiting areas, bathrooms and operating rooms. The cleaning and re-cleaning amounts to more than 2 million square feet per day.

Elizabeth Parker, an environmental services technician at Our Lady of the Lake, repeats her rounds every 15 to 30 minutes. She disinfects everything from IV posts to computer desks.

And like Jones, Parker has her own haunting memories of the virus.

She caught COVID-19 at the beginning of March. It was before anyone in Baton Rouge realized the virus was spreading in our community, back when it was hard to even get a COVID test.

She was sick for two and a half weeks. She had unrelenting body aches, loss of smell, a sore throat and a 102.9 degree fever that just wouldn’t go away.

“It was actually life changing for me,” she says. “It’s so many phases your body goes through when you have COVID. It was like an up-and-down roller coaster. One minute, you’ll feel OK. The next minute, it’s like a crash and burn.”

Parker was worried she would pass the virus on to her fiance and her young kids, so she separated from her children for two weeks.

The scariest part by far, though, was watching one of her friends fight the virus at the same time as her. A certified nursing assistant who works on her unit was on a ventilator for three months.

The scariest part by far, though, was watching one of her friends fight the virus at the same time as her. A certified nursing assistant who works on her unit was on a ventilator for three months.

“The toughest thing,” Parker says, “was seeing her intubated and really sick every day.”

After Parker recovered from the virus, she was asked by her manager if she felt up to working on the COVID unit. The decision was one of the most difficult she’s ever had to make. But she accepted because she wanted to play a part in keeping everybody safe.

Outside of work, the 27-year-old has dramatically altered her social life. Before, Parker says, she was a “get-up-and-go person.” She liked to go out. Now, all she does is work, come home and stay home. She limits where she goes, how long she goes there and who comes to visit her house. She does not want to get the virus again—or risk spreading it to someone else.

She knows what it feels like to clean a room a patient has died in. It’s the hardest thing, she says, to go from seeing that person alive in the unit every day to watching as they’re carried away in a body bag.

“I feel like people outside hospitals’ COVID units, or who have not had the virus, don’t see the virus like I see the virus,” she says. “I’ve seen how it actually affects a human. How somebody could be OK one minute, and the next minute they’ll feel horrible.”

Parker has watched patients die within three hours of arriving at the hospital. She has heard the calls to families telling them their loved ones will never come home again.

Jones shares similar feelings, especially when she worries for her 17-year-old son. She always encourages him to remember his mask. She doesn’t want either of them to get sick.

“That’s why we [clean] every surface, every wall, every item in the room,” Parker explains. “We have to be more cautious about how we clean and how thoroughly we clean.”

When asked what she wishes people knew about her job, Jones becomes pensive.

“A lot of people make it seem like housekeeping or cleaning is not a good job,” she says, “but I really don’t mind what I’m doing. I enjoy my work days here.”

The most rewarding thing for environmental services workers has been getting recognition from their coworkers. It’s acknowledged that they’re tackling some of the toughest work imaginable on the frontlines of a global pandemic.

“It’s really a blessing to have the group of individuals that I have today working for me. They truly care about providing a safe environment and quality patient care,” says Johnathon Calvey, Ochsner’s director of environmental services. “Everyone on my team is passionate about what they do.”

And that passion is the very key to keeping the hospital running properly during the pandemic—and saving lives.

“A lot of people don’t have the bravery or the heart to work on the COVID unit throughout the whole pandemic. But without the environmental services team keeping everything clean and disinfected, the hospitals would be a lot less safe,” Parker says. “We prepare for the worst, but give our best. We are essential.”

This article was originally published in the December 2020 issue of 225 magazine.