End-of-life doulas help clients plan a ‘good death’

EXPLAINER

What is an end-of-life (or death) doula?

End-of-life doulas (EOLDs) provide non-medical, holistic support and comfort to people preparing for, or experiencing, end-of-life by offering education and guidance; emotional, social and spiritual care; logistical and practical assistance, and more—before, during and after death. End-of-life doulas complement and supplement the work of family and other caregivers (including hospice providers).

Source: the National End-of-Life Doula Alliance![]()

Karla King considers herself to be a healthy person. She’s practiced yoga for 30 years and eats right. She’s involved in the community and has been a longtime volunteer at both the Baton Rouge Gallery and WHYR community radio station. The former performing arts costume designer has pursued new creative outlets in retirement, like painting, learning the bass guitar and making jewelry.

|

|

There’s no reason to believe she’ll die anytime soon.

But last year King, 66, hired a “death doula,” a trained professional who helps clients create a plan for their final days. Working alongside physicians, nurses and hospice professionals, an end-of-life doula provides emotional support to those who are dying, helping them think through and document preferences that go beyond last wills and testaments and medical directives.

It’s based on the work of birth doulas, who support families through pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period, a service that has grown in popularity across the country, and in Baton Rouge, since the 1980s.

Death doulas tailor their work to each family’s needs. Their services could include documenting funeral details, identifying where a person wants to be when they die, who they want at the bedside, what stories they might want to record for posterity and any other instructions regarding their death and dying process.

“It’s a strange thing, but when you pass that age 65 mark, and you’ve lost people around you, you see what can happen when things are left undone,” says King, who is married and has an adult stepdaughter. “It can leave a burden of suffering and unnecessary grieving on the living.”

A good death

Last September, King hired Robin Palmer Blanche, a certified end-of-life doula in Baton Rouge.

It’s a second career for Blanche, a young adult novelist and former movie and television producer who has worked extensively with Lifetime and MTV. Blanche moved to Baton Rouge in 2013 after meeting her future husband, a Baton Rouge native, while she was shooting an MTV movie in New Orleans. She continues to work as a television screenwriter.

Blanche, who has two elementary-age children, says she was drawn to the end-of-life doula field after a personal health scare in 2021. Blanche was diagnosed with stage one follicular lymphoma, and while the cancer was treatable, the episode made her consider what she would do if her own death was imminent, she says.

“It made me think, ‘If I were to find I had a finite amount of time to live, how would I want to spend it? And what would I want to leave behind to lessen my family’s grief?’” Blanche says.

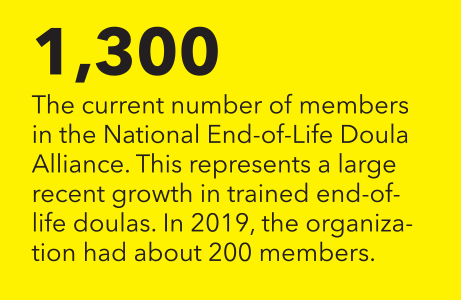

While it’s still a niche field, death doula numbers have been growing since the pandemic. The National End-of-Life Doula Alliance currently has about 1,300 members across the country. In 2019, it had about 200.

The option to use a death doula is slowly becoming better known, says The Hospice of Baton Rouge Executive Director Catherine Schendel, who recruited New York-based death doula and TED Talk speaker Jane Whitlock to address a palliative care symposium the local nonprofit hosted a few years ago. A big part of a death doula’s work, Schendel says, is providing emotional support through a difficult time, while also helping families remove uncertainty about a dying person’s wishes.

“Knowing what your loved one would have wanted you to do is so important because there’s a lot of guilt that complicates things when (survivors) aren’t sure,” Schendel says. “For the family, it’s only later that they’re left with those things to unpack mentally, and they wonder, ‘Did I make the right choices and do the right things?’”

Blanche completed her first death doula certification in 2021 with New Jersey-based International End of Life Doula Association and is trained in end-of-life support for both dementia patients and terminally ill children. After the pandemic pushed many trainings online, Blanche has been able to earn certifications from home in Baton Rouge. She’s currently working on one concerning grief counseling. She’s worked with four clients who have since died, and is working with about six more who are in various stages of planning.

Blanche uses her background as a writer to help her clients document everything from detailed advanced directives to extensive family histories. She also provides the latter service to older clients around the country who aren’t sick.

The concept of a “good death” versus a bad one is something Blanche has pondered most of her life. At age 6, she lost her mother to suicide.

“It was so sudden,” she says. “And the whole process, especially the grieving process, was truncated. She died, and it was never talked about again. There were a lot of repercussions to that, and I felt cheated in a lot of ways.”

By contrast, Blanche’s father’s death in 2019 gave her a chance to see the value of reaching a peaceful closure. He was diagnosed with stage four non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and died a few months later in Phoenix, she says.

“His death was so life-affirming because we had every conversation we wanted to have, and there was nothing left unsaid,” Blanche says. “Every time I got on the plane to come back to Baton Rouge, I thought, ‘If I get a call when I get off the plane that he’s gone, we’re good. We’ve said everything we needed to say.’”

Baton Rouge physician Kate Freeman, who treats patients 65 and older, says that while conversations about death are uncomfortable, it’s important to speak openly and frankly about it.

“We seem to regard death as optional in our society, not inevitable,” Freeman says. “Having these conversations gives people a more active role in the decisions they and their family might have to make. It gives people a chance to say, ‘What would a good death look like?’”

Owning the process

King initially met Blanche through mutual friends, but when she learned about Blanche’s death doula work, she was intrigued and hired her.

“I felt really comfortable with Robin,” King says. “My husband and I have had our wills for many years, but I wanted to get this stuff on the table.”

King says she’s working with Blanche to think through the type of funeral she wants to have (it’ll be unconventional and won’t involve a funeral home), what she wants done with her remains and how long she would want to prolong treatment for a terminal illness. She’s even considered the last garment she might wear.

“A friend of mine, who is also a costumer, sent me something about custom designs for end-of-life garments, and I thought, ‘No, I’m fine with just a clean white sheet,’” she says.

King says she likes the idea of weighing every aspect of her final days rather than defaulting to social norms.

“We’re only given certain options, but there are many more out there about how we die,” she says. “As I’ve aged, I guess I’ve become very realistic about life and death. How can we honestly say we’re living if we’re not preparing for this inevitable thing that we aren’t going to escape?”

Blanche named her end-of-life doula business You Were Here, because she says the chief concern among the dying is that they’ll recede in the memories of their loved ones.

“Studies have shown that when people think about dying, their biggest fear is not pain. It’s not what’s going to happen to them in the afterlife. It’s the fear of being forgotten,” Blanche says. “So this is about being intentional with that remaining time and documenting how you want to be remembered.”

For King, the regular meetings with Blanche have been cathartic and even “exciting,” because it’s allowed her to take control over decisions most people don’t want to think about.

“I’m someone who is very curious,” King says. “I want to think through all my options.”

And that’s the bottom line, Blanche says. Death doulas are there to help a person in the final phase of life feel supported, and to some extent, still in control.

“We’re powerless over dying,” Blanche says, “but not we’re not powerless about how we spend that time before we die.” For more info, visit youwereheredoula.com and nedalliance.org.

This article was originally published in the January 2023 issue of 225 magazine.

|

|

|