Molly Taylor is making something.

This morning, the musician and jewelry designer stands at the drill press in a tie-dyed camisole and a pair of cut-off shorts, her hair pulled up to keep it off her neck. The air trapped by the brick walls of the woodshop is thick and warm, heavily scented with cedar and walnut. On a Sunday in September, it’s enough to break a sweat.

But the heat doesn’t seem to bother her. She’s making a pair of earrings today—a commissioned piece using spalted pecan—under her jewelry brand, Beneath the Bark. She’s already chosen the perfect scrap of wood from one of the milk crates she keeps in a corner of the shop, and now she’s hollowing out a circle in it.

Next comes a trip to an enormous band saw, where she turns the wood in small, painstaking increments against the blade to cut out the round piece. Then it’s off to the belt sander to smooth out the edges, back to the band saw to split it in two and a return to the drill press to carve out tiny holes for the hardware that will make the earrings wearable.

All that is before the first coat of resin. It’s a lengthy process to make one piece of jewelry, but the handcrafted details and subtle character of the wood make her pieces stand out to clients from all over Baton Rouge and the region.

Behind the woodshop, stacks of massive tree slabs tower over the yard. Many more are drying out in a homemade solar kiln Taylor and her partner Andrew Moran affectionately call “Hot Larry.”

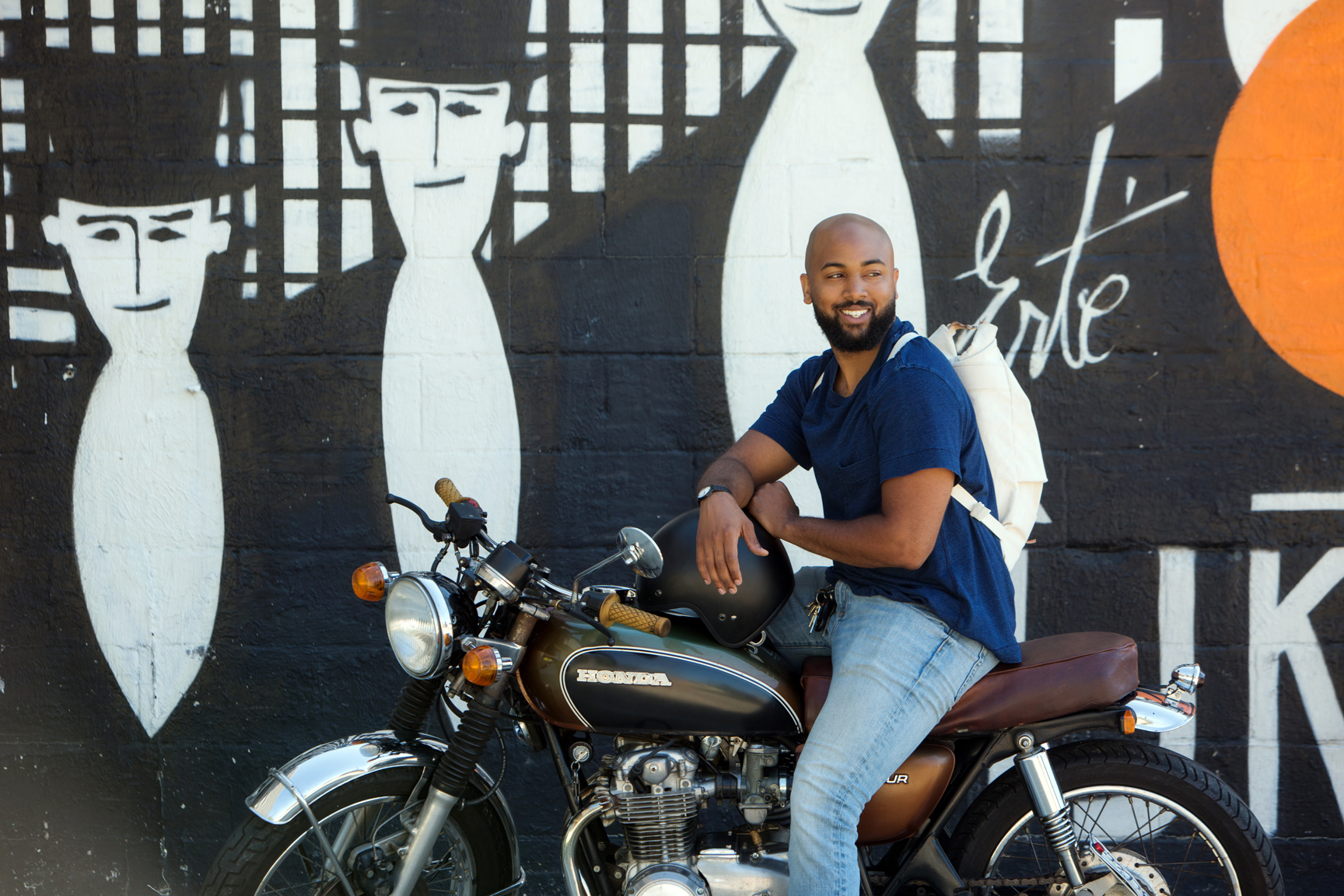

Moran salvages downed trees and stumps from all over Baton Rouge and as far as Lake Maurepas for his own woodworking and furniture design business, Midcity Handmade.

Their shared workspace is the ground floor of the historic Book Exchange building on 19th Street that Moran bought, renovated and repurposed, constructing a two-bedroom apartment above it by hand. Across the street from its white brick facade, a family shouts with laughter on their front porch, ribbing each other over lunch. Just down the road sit Circa 1857 and The Guru, two of Mid City’s biggest creative hubs.The two say they spend “99.9%” of their time in this area of town. Taylor bartends at Radio Bar and will celebrate the release of her first album with a show at The Guru. Both artists walk their mutts, Blue and June, through the neighborhood every day. You might catch them along 19th Street, waving to a neighbor on one of their walks.

“I feel like Mid City is going to be an artist community,” Taylor says. “Three years from now, when you say, ‘I live in Mid City,’ people are going to automatically think of color and art and bikes.”

They’re the poster children of Baton Rouge’s growing subculture: a “maker’s village,” pockets of indie makers, small businesses and ambitious creatives filling close-knit neighborhoods and supporting one another, tied together by walkable and bikeable streets. And they’re just getting started.

“What you makin’ today, Miss Molly?”

The greeting is always the same when Molly Taylor steps into her go-to hardware store, Our Hardware on the edge of the Garden District. Co-owner Bridgette Edwards knows every person in the store by name, and she accepts both “Miss Bridgette” and “baby” from her customers.

“It’s just refreshing. You walk in, and they remember you. They say, ‘Hey, how you doing? What can I help you with?’ … It’s keeping the country in the city,” Taylor says. If she’s looking for a particular stain for a piece, she can let one of the owners know and come back a week later to find it stocked on the shelves.

“Country in the city” is a good way to define the spread of maker culture in neighborhoods like Mid City, Perkins Road overpass and parts of downtown in recent years—the friendliness and intimacy of a small town with the resources of a big city.

It’s a quick trip by foot for Taylor to Our Hardware, and sometimes when she’s in the neighborhood, Taylor will grab a coffee with Madeline Ellis of Mimosa Handcrafted, another established maker and a mentor of Taylor’s.

Formerly a landscape architect, Ellis first got into jewelry-making to scratch an itch: Waiting for her landscape designs to be built took too long, and she missed the “primal” feeling of making something by hand and seeing it instantly brought to life.

She left her job to pursue Mimosa in 2013, and she now operates her business out of a studio behind her home, tucked just away from the Perkins Road overpass. Every element of her life is homegrown and sustainable, from her home decor to her backyard agriculture to her business.

In just a few years, she’s grown a hobby into a full-time job for both herself and her husband, shipping pieces out for retail as far as Georgia. She’s a regular at art festivals like White Light Night, Ogden Park Prowl and North Gate Festival, and she frequently visits regional fests and pop-ups to peddle her products.

But even with her own growing business to nurture, Ellis didn’t hesitate to show Taylor the ropes. There’s no element of competition in Baton Rouge’s maker community, Ellis says, only camaraderie and shared resources.

“Finding out that you’re not alone,” Ellis says, “finding other people like [you], thanks to social media and doing arts markets and pop-ups—it’s been encouraging and exciting. ‘Hey, there are these people that are into the same thing I’m into, and they want to have chickens, too!’ It’s not just about the making of the thing. It’s about bringing yourself back to basics. … We all support each other, and it feels like the old days.”

The web of creativity spirals out in all directions. Ellis considers Baton Rouge artist Kathryn Hunter, who makes stationery, notebooks and other items through her business Blackbird Letterpress, her maker “mom.” Taylor’s boyfriend, Moran, partners with local craftsmen like leatherworker Damien Mitchell, who’s done custom leather drawer pulls for Midcity Handmade furniture.

All of them frequently run into one another and countless other familiar creatives at hubs like Radio Bar or Magpie Cafe, where trade secrets are swapped and collaborations are born over beers or lattes.

“A lot of creative fields, in this area in particular, it would be hard for it to grow on its own. It’s not New Orleans,” says Mitchell, a newer face to the local maker scene. “So for us to be able to grow and build our own businesses, we have to connect with other people who are doing the same thing so that we can do these collaborations and network among each other to broaden the scope of our audience.”

Ellis, who’s been deeply entwined in the maker community for years now, still depends on her fellow makers to keep her going, whether it’s taking advice on accounting apps or launching her favorite collaboration, a notebook and necklace set with Blackbird Letterpress.

“To borrow from bee terminology: It’s cross-pollination,” Ellis says. “When we do a project together, then all of their [followers] see my stuff and all of my people see their stuff, so we get to share customers that way. But then also, it pushes you to do something outside of your comfort zone. It’s always rejuvenating and exciting to do something different and learn from them.”

The boom of the maker community in the past five years hasn’t just been built on creating products. It comes from creating a network of fellow makers, engaging customers, tapping into today’s trends of all things handmade and drawing on strong local roots to garner the support of the city.

It’s impossible to find a seat.

Ogden Park Prowl, one of Mid City’s biggest annual events, has filled Radio Bar to the brim, with autumn cocktails flowing and amateur art collectors foraging for a piece from local arts collective Elevator Project’s Sweep the Studio sale out on the patio.

Outside, along Government Street and in the Ogden Park neighborhood behind the bar, booths pepper yards and street corners—pottery, soap, jewelry, jams. If you want it, chances are some enterprising local makes it and has set up shop at the Mid City art festival.

Here, local makers get the chance to meet up with customers face-to-face, build relationships and put a human heart and soul behind the brand. That’s how Ellis has met loyal return customers who stuff stockings with Mimosa charms every Christmas, and it’s how Taylor has spread Beneath the Bark beyond her studio.

If you ask Blackbird Letterpress owner Hunter, she’ll tell you that markets, festivals and pop-ups like these have made her the maker she is today.

When Hunter first settled in Baton Rouge a decade ago with her husband and a letterpress from 1904, she became one of the first trailblazers of the city’s maker culture. Ten years ago, the Shaw Center for the Arts was newly opened, art hops hadn’t yet exploded, much of Mid City was underdeveloped and her best shot at a venue was her husband’s workspace on Main Street at the edge of downtown.

Her earliest and most valuable experiences in the maker community came from pop-up shows there and Saturdays at the Arts Council’s monthly Arts Market.

“That was where you [first] saw real makers,” Hunter says of her early days at the Arts Market.

Since then—particularly since the 2011 release of FutureBR’s vision to make the Government Street corridor an integral part of redevelopment for the city—art events like White Light Night have ignited a new fire of community interest. The annual block party all across Government Street now includes more than 50 businesses and packs thousands of people into Mid City, while new neighborhood festivals like Ogden Park Prowl spring up and hops like Hot Art, Cool Nights bring in more maker booths each year.

Josh Ford of Giraphic Prints, too, has seen that transformation. Ford purchased an unused building on Government Street in 2015 for his growing screenprinting business. They expanded the space and soon moved in two more creative tenants: Gaudet Bros. hair salon and Slash Creative design studio. In addition to creating his own hub of creativity in Mid City, Ford and his crew have been riding the wave of art hops.

“We do White Light Night and Hot Art, Cool Nights and everything,” Ford says. “Those have been really great events for us, especially now that Gaudet Bros. and Slash have been up and running up front. The last one we did was really awesome; we basically had a block party.”

With creatives like Ford investing in their neighborhoods and new opportunities arising daily, the spread of what Taylor calls the “creative flu” has accelerated. Ford’s business has grown so much that he now employs several local makers, with a team of half a dozen designers and printers on the Giraphic Prints team.

And with growth comes a new pride in these parts of town—a sense that Baton Rouge is, of its own right, “cool.”

With every inch of redevelopment in Baton Rouge in the past five years, the same questions have come up: Can you walk it? Can you bike it?

Walkability and bikeability have proven to be crucial elements of the maker’s way of life and part of the foundation of the cultural movement. Taylor and Moran walk to their hardware store. Many of Ford’s employees bike to work. Nearly every day, Ellis strolls just down the street to get groceries at Bet-R—where the staff has known her two kids from birth—or across Perkins Road to The Big Squeezy for a juice or coffee.

Haley Blakeman, director of implementation at Center for Planning Excellence, has helped lead the push for such neighborhood upgrades. CPEX has worked with the Department of Public Works, BREC, BRAF and advocacy groups to revamp parts of the city to enable foot and bike traffic, including building bike lanes and slowing car traffic for pedestrian safety.

Blakeman has helped organize Better Block events in Mid City and the Perkins overpass area, where she and the team at CPEX take over a neighborhood for the weekend, demonstrating the possibilities with temporary bike lanes, better landscaping, green space and other features. The Government Street Better Block event in 2013 helped push the city to develop plans for that Mid City corridor—which connects many of these maker’s villages—including bike lanes, pedestrian crosswalks and medians.

“Sometimes it takes people seeing it with their own eyes, not just seeing it in theory but seeing how it works, seeing how it functions, and that you really can drive on the street and have a bike lane at the same time if you do a few things differently, and how it slows down traffic, how it connects you to the businesses,” Blakeman says. “Once they see it, they feel a lot more comfortable. The unknown is what’s most scary.”

It’s critical, she says, not just to have connections between neighborhoods within Mid City but to connect those routes to downtown and the Garden District, to plan and build a complete city that allows walk-up businesses, pop-ups and a culture colored by creatives.

Plenty of progress has been made already, and neighborhood businesses are prepping for changes in traffic in a variety of ways, such as installing bike racks at their storefronts.

Just in the past year, we’ve seen the opening of trendy spots like Goûter Restaurant, the brick-and-mortar location for popular food truck Curbside Burgers is nearing completion and plans are moving forward for a beer garden and the collaborative food hall at White Star Market, all of which are on Government Street. The city is working on a redesign of the six-acre Entergy site, also on Government, with plans for it to become a mixed-use hub.

Small upstarts like Tredici Bakery & Cafe in Capital Heights now cull much of their clientele from neighborhood walkers, while shopping centers like those housing Giraphic Prints consolidate creativity into easily accessible pockets.

With all this activity, it’s easy to see why property values in the blocks around Government Street have increased.

“The traffic on 19th Street is unreal. Five o’clock, the cars are backed up from Government Street to North Boulevard, just inching by,” Moran says, picturing redevelopment that would benefit both new arrivals and longtime neighborhood residents. “I just imagine somebody being able to turn on to 19th and [walk] to some little dive restaurant or dive bar. … It’s getting there. I feel like in the next couple of years, from where we live, you’ll be able to walk to all kinds of places.”

At the heart of this maker’s village, there’s a simple philosophy, as spoken by veteran maker Hunter:

“Make where you live where you want to be.”

That doesn’t mean making a city into something it isn’t, like trying to force Baton Rouge into the mold of famously creative cities like Portland or Austin. It means working within the parameters of what you’ve got, holding onto those once-vague but now-strong neighborhood identities and investing in Baton Rouge to make it Baton Rouge at its best.

The infrastructure needs are a bit daunting, especially for a city still reeling from a flood. But almost every person with a hand in the creative clay has an idea of how to make the city more functional.

Taylor and Moran would love to see more walkability. Mitchell dreams of more bike lanes near his home and studio in the Garden District. Ellis envisions a massive creative workshop where newbie makers can immerse themselves in trade, locals can get a firsthand appreciation of handcraftsmanship, and makers can share space and inspiration. Ford believes more beautification projects like planters along the streets and murals would increase foot traffic throughout Mid City and boost business.

Looking at all the possibilities, Blakeman and her team feel invigorated—but we can expect to see smart, strategic growth by increments, not massive overhauls all at once.

“We work within politics and we work within budgets. We understand both sides of that,” Blakeman says. “So there are so many incremental things you can do building up to that. Like crosswalks—it’s just paint. They’re really inexpensive, but they’re so much safer.”

The idea of investing in these makers’ communities isn’t just about the pockets of town themselves, but about enriching the culture of the city at large, which brings benefits like keeping young professionals in the city, boosting tourism, enabling neighborhood relationships and creating a stronger sense of identity for the city.

“I think it was [legendary graphic designer] Milton Glaser that said, ‘Art is what gives people something in common,’” Hunter says. “It’s something that connects people to each other. Everyone has something to gain from art and artists and makers in the community. … And I feel like Baton Rouge is supporting this. The Arts Council is doing what they can. [Redevelopment agencies are] doing great work. I think we’ll only grow.”

Blakeman and CPEX are part of that growth, focusing in the near future on connecting the dots between neighborhoods and the rest of the city. Her vision for Baton Rouge is vibrant, bold and ambitious.

“I would love for the corridor down Government Street to just be lively day and night. To be colorful, to be open, for people to be able to walk down the street but also for people to be able to drive down the street more safely. New restaurants, shops of all kinds, artists, but also people who just live on it,” Blakeman says. “And just connect that all the way to downtown, instead of just downtown here, a little pocket here, a park down here. And there are plenty of corridors around Baton Rouge that need the same thing, and each one could have their own identity.”

It can be done, she says, and accomplished in a way that preserves Baton Rouge’s character and sets it apart from other cities rather than trying to be more like them. These indie makers, with their homespun contributions to the city and their locally sourced lifestyles, are leading the way.

“We don’t need Government Street to be like Magazine Street,” Moran says. This time he and Taylor are sipping beers in a booth at The Radio Bar, him with sawdust on his T-shirt and her with one of her handcrafted wooden charms around her neck. “We need Government Street to be like Government Street.”

“Let Baton Rouge be what Baton Rouge is going to be,” Taylor adds. “It’s not even finished evolving. We’re still creating.”

More on local makers

• When and where hubs for creatives have popped up in recent years

• Where bike paths have been completed – and where we think they should go next

This article was originally published in the November 2016 issue of 225 Magazine.