Here’s how one group aims to lower accidental opioid overdoses in Baton Rouge

Correction: This article has been updated for accuracy, changing the name of H&E Equipment Services. It is not H&E Equipment Sales, as previously reported. 225 regrets the error.

Tonja Myles is sipping coffee outside Starbucks when a young woman spots her and approaches.

“Thank you for all you did,” she tells Myles. She pulls out her phone to show Myles a picture of her child. She says she and her boyfriend are doing well in recovery, living clean and raising their 7-month-old daughter, who adores her dad, thanks to Myles’ support.

As she walks away, Myles says softly, “it’s just good to see them on the other side.”

|

|

Myles, a former addict, a minister and a veteran, is well-known in Baton Rouge as a champion for substance use treatment and mental health awareness. She founded Free Indeed in 2004, the first licensed faith-based outpatient treatment center in Louisiana. And her ministry of a similar name, Set Free Indeed, which she runs with her husband, Darren, operates numerous community programs and campaigns that have led scores of people to sobriety and recovery.

Since 2020, the ministry has doubled down on its local public outreach, creating the When You Are Ready initiative in response to the growing opioid, and now fentanyl, crisis. It’s something Myles knows personally.

“I’ve been in recovery for about 38 years, so this is not just a career,” Myles says. “It’s a calling for me. I know how it is to be in the throes of addiction, to feel helpless. That you’re by yourself and that you will never get out of that bad space. I wake up every day to push hope.”

“The fentanyl problem is like nothing we’ve ever seen in our country.”

Set Free Indeed founder TONJA MYLES

The Baton Rouge native has been a pioneer in creating a faith-based approach to substance abuse counseling. It was something she sought when going through recovery from a drug problem that had escalated to include crack cocaine.

“To me, having a faith-based approach just gives people a choice, an option, that some of them are looking for,” she says.

Myles was recognized for her work by President George W. Bush during his 2003 State of the Union address. And since then, Free Indeed has become a model for 28 other similar treatment centers in the state and around the country.

While Free Indeed is a standalone outpatient clinic, the Myles’ ministry, Set Free Indeed, is focused on spreading the word that there are nonjudgmental substance abuse and mental health resources for those who need them. Myles says that it’s been important for the ministry to adapt its programs to what’s happening on the street and behind closed doors. She has written a toolkit for churches, synagogues and mosques to grow their knowledge about how to help those with substance use problems.

Right now, that means doing something to curb the city’s overdose rate.

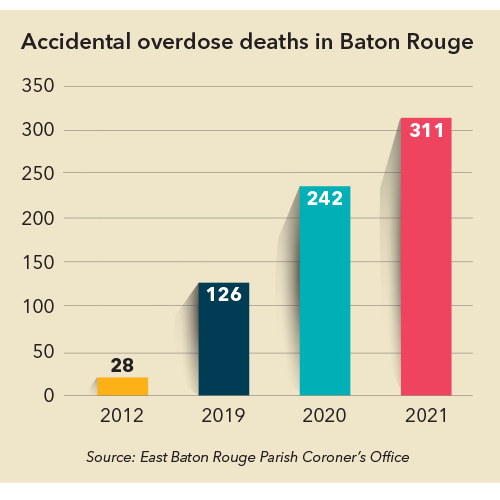

Last year, overdose deaths were at an all-time high in East Baton Rouge Parish, after rising every year for nearly a decade, according to the EBR Coroner’s Office.

In 2012, 28 people died of accidental overdoses in East Baton Rouge Parish. By 2019, that number had risen to 126. It nearly doubled to 242 in 2020, as the country continued to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic. And in 2021, overdose deaths rose again to 311.

That grim trend prompted Myles and her team to launch When You Are Ready, an outreach effort in which volunteers and peer counselors set up tables at local big box stores and stand in neighborhood hot spots with high drug use rates to bring awareness about the dangers of overdosing.

“As an ordained minister, I’ve buried a lot of people who have died of overdoses,” Myles says. “So that’s why we came up with When You Are Ready, to provide resources to people, and to go where they are.”

Opioid deaths have been at the center of Set Free Indeed’s efforts for many years, but the highly potent synthetic opioid fentanyl has brought the overdose issue to a new level of urgency, Myles says.

Fentanyl has been, and continues to be, produced legally in the United States as a painkiller, particularly for cancer patients. But like other opioids, it ends up on the black market and is sold either alone or laced with other drugs, like heroin or marijuana. It comes in many forms and can be difficult to detect, Myles says. That makes for a deadly combination, because the substance is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

“We want to tell people, ‘First of all, it will kill you,’” Myles says. “You don’t know what you’re getting. It’s not worth it. You’re playing Russian roulette with your life.

Throughout the When You Are Ready campaign, Myles has been working closely with the East Baton Rouge Crimes Strategies Unit, an interagency law enforcement unit that shares data with Set Free Indeed every week about where overdoses are happening in large numbers.

“Then, our team appears in those hotspots,” Myles says. “We take resources, we take Narcan (the emergency drug to treat narcotic overdoses), we go to businesses, we go to schools, we go to churches. We go to every place that we can to spread awareness.”

By mid-October of this year, 227 individuals in the parish had died of accidental overdose. It could suggest a slight decrease in 2022, though that won’t be known until the end of the year.

Myles is hopeful about the organization’s ability to meet people where they are.

“I think that’s why we’re seeing some numbers decrease,” she says.

Myles has partnered with H&E Equipment Services, which funded a $100,000 ad campaign to promote When You Are Ready’s work.

“The fentanyl problem,” Myles says, “is like nothing we’ve ever seen in our country.”

Its potency has a tragically long reach, impacting the most innocent of bystanders.

On Halloween night in Baton Rouge, a 1-year-old child died of a fentanyl overdose, the second such death following the death of a 2-year-old by the same cause in August. Both cases have brought attention to dismal case worker shortages at the Louisiana Department of Child and Family Services, but they also point to the nagging number of adults struggling with drug addiction.

In the meantime, Myles and her team of six are in the community every week, speaking to groups and manning tables at Walmarts, Office Depots and other locations. They greet people without judgment, passing out cards that provide quick information about where to go for help.

“Addiction is real,” Myles says, “but so is recovery.”

This article was originally published in the December 2022 issue of 225 magazine.

|

|

|