Period poverty: The taboo topic Baton Rouge activists want to tackle head on

A woman’s monthly period is a basic part of life. Without it, humanity would cease to exist.

Cue the embarrassment. The scarlet cheeks. The burning desire to find something else to read—and fast!

Even in 2023, menstruation remains an awkward topic rarely uttered in mixed company. But it’s one that’s on the minds of a growing number of activists in south Louisiana. They’re calling attention to an issue that’s been plaguing women and girls for years: An alarming number of females living in poverty lack the financial resources to purchase basic menstrual products. It often results in missed school and work, as well as the risk of urinary tract infections and other health issues.

|

|

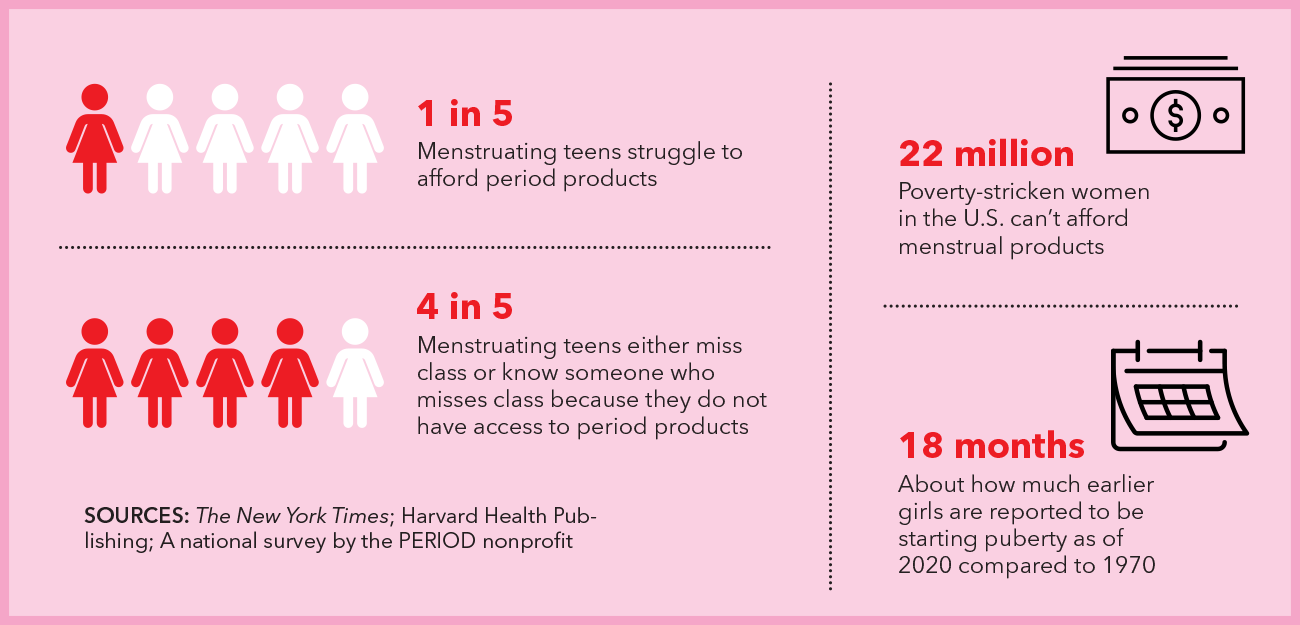

“Until very recently, this issue has been very hard for people to talk about,” says Sherin Dawud, co-founder of local nonprofit Power Pump Girls, which champions what’s referred to as period equity. “But the moment you’re like, ‘What would I do if I went months and months without tampons and pads and had to deal with my cycle?’ you get someone’s attention.”Period poverty is felt across a wide range of ages, especially now with some girls experiencing a first period at a much earlier age than in past generations. Starting around the 1970s, studies across the globe have recorded a 3-month-per-decade drop in the onset of puberty in girls. Louisiana families in poverty often cannot afford to purchase period products for the household’s women and girls, and these products can’t be purchased with SNAP benefits.

One in 5 menstruating teens struggles to afford period products, while 4 out of 5 either miss class or know someone who misses class because they do not have access to period products.

Women and girls in the Capital Region are facing these challenges, too.

Dawud and fellow cofounder Raina Vallot have spent the last few years spreading the word about period poverty in Baton Rouge. With motos like “Investing in women, period,” it’s one of the nonprofit’s main planks. The group is working with national manufacturers of period products, and has plans to launch a small grant program that will distribute such products to community groups in Louisiana this spring.

Similarly, Baton Rouge activist Deirdre Mwalimu and her organization, Network of Women NOW, held its inaugural drive for period products last fall. Mwalimu hopes to make products available to college students in need.

“One in four college students face period insecurity,” Mwalimu says. “When we give feminine hygiene products to the LSU Food Pantry, for example, they’re gone within 24 to 48 hours.”

Some Louisiana activists and elected officials are bringing attention to the issue across the state, as well.

Last year, Gov. John Bel Edwards signed into the law the removal of the “pink tax” in Louisiana, which meant period products would no longer be subject to state sales tax. The law went into effect July 1, 2022, and included a local option for municipalities to also remove their sales tax, which has since taken place in Baton Rouge, Shreveport and New Orleans. Dawud and Vallot were among the activists who worked closely with the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Aimee Freeman, (D-New Orleans), to get the bill passed in 2021.

In this year’s legislative session, Freeman will re-file another period poverty-related bill she last tried to get passed in the 2022 session. The bill would encourage public schools to make free menstrual products available to students. In 2022, it successfully passed the House, but stalled on the Senate floor and was not voted on before the session ended.

Freeman says that while she worked with a strong coalition to get the pink tax lifted, and successfully garnered bipartisan support in the House for the free menstrual products in schools bill, it may be challenging to get the bill passed this year.

“It can take years, sometimes, for a quality piece of legislation to get passed,” she says. “I plan to make it one of my five non-fiscal bills. But this is an election year, and I have no idea what will happen.”

There are currently 14 states and local jurisdictions with proposed legislation to ensure menstrual products are readily available in school bathrooms. But most of these bills don’t correspond with funding, leaving it up to school districts about how such programs will be implemented. Similarly, the Louisiana bill doesn’t come with funds to support the purchase of products. It’s unclear at this point how it would be paid for. Activists say it should be considered just like other bathroom supplies.

“It’s essential the same way toilet paper and paper towels are found in every restroom—because they’re necessary,” Dawud says.

In the meantime, Power Pump Girls and the Network of Women NOW are continuing to raise awareness and hold product drives.

Mwalimu says Network of Women NOW is collecting donations of period products at The Red Shoes and Athleta.

Dawud says the Power Pump Girls are also launching a new initiative this spring that will address one of the other issues related to period poverty: education. She says they’ve been deliberate about not broaching anything that could be construed as controversial, like sex education. Rather, the program is intended to help young people who lack resources and parental direction to understand what’s happening in their own bodies.

“It’s going to be a fun, modern, relatable education course that talks about what menstruation is and what hormones are,” Dawud says. “We think about families that might have a single dad, and know it will be helpful for them and others.” networkofwomennow.org and powerpumpgirls.org

This article was originally published in the February 2023 issue of 225 magazine.

|

|

|