On a weekend trip with a friend last fall, I was reminded how often we pass a refuge, preserve or wildlife management area in south Louisiana and consider it off-limits. As if the only people allowed inside are researchers documenting the growth of longleaf pines or monitoring a protected species of warbler.

And if not researchers, we assume it’s the hunters, fishers or trappers who get permits to tread those tracts of land.

For those of us without access to a boat or ATV, unless we see a visitor center or a clearly marked trailhead, it’s just a seemingly vast protected wilderness we’ll only glance at from the road.

On that weekend trip, my friend and I were driving along Highway 90 between Lafayette and New Orleans and had time to kill. The fall weather was mild and sunny, so we searched our phones for places to go for a short walk.

We soon ended up at Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge near Franklin. We parked in an empty trailhead lot and started down a boardwalk that stretched into the cypress tupelo swamp. The path was short, but well-maintained, curving through where swamp blended into marsh and offering several interpretive signs along the way.

We learned that black bears are part of the refuge’s conservation mission, though we didn’t see any. But there were cattails taller than any I’d seen before, long stalks of marsh reeds with fluffy pale seedheads at the top that swayed in a breeze, and hundreds of birds chattering in the branches above us.

It left an impression. Here was a place far removed from the hubbub of urban life, not really on the tip of anyone’s tongue as an outdoors destination, but one we’re still trying to preserve. And here’s a spot for you to peer into it, to look in on a massive expanse of wild land that’s difficult to access otherwise.

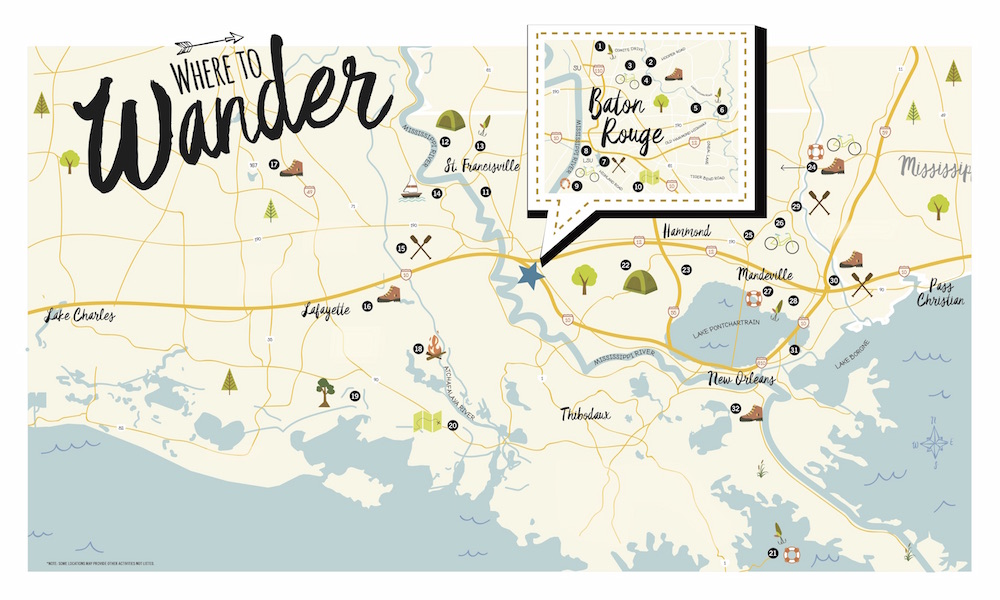

In researching public lands to put on this map, I spent a lot of time browsing websites for dozens of state-owned and federally managed properties in south Louisiana. In many cases, it’s hard to determine what the general public can do there.

Top billing is focused on hunting and fishing regulations. The passive explorers—those of us who just want a quiet moment in nature—often have to search for the finer print.

But I’m seeing more and more how we’re finding new ways to get out and experience those places. We’re organizing paddle trips on lakes and bayous to raise awareness about conservation, pushing for more bike trails to link us to public green space around the parish, and even racing each other on standup paddleboards down the Mississippi River—a place that once seemed reserved only for ships and barges.

And down at the Bayou Teche refuge, a “Friends of the Bayou” group hosts yearly educational hiking and paddling trips that bring you further into the area’s beauty than I was able to go that fall day.

As we continue to learn the benefits of time spent in the fresh air, of showing reverence for our natural places, I’m hoping more of us share what we’re discovering on our treks so that we all have a reason to explore the possibilities just a short drive away.

—Intro By Benjamin Leger

Explore the Capital Region’s backyard with 225:

THE PATH

・32 parks, refuges and more to explore around South Louisiana

THE AGENDA

・Beat the dreaded Southern summer heat with these cool Capital Region activities

・Thanks to Baton Rouge’s geocachers, there are hidden treasures all over the city

・Where to see great outdoor art in Baton Rouge

・Exploring BREC’s Botanic Garden at Independence Park

THE STORIES

・How False River became home again for one writer

・Conservationists talk preserving wild spaces in Baton Rouge

・Adventures in bird watching at BREC’s Bluebonnet Swamp Nature Center

・Finding Fantastic Mr. Fox in Baton Rouge

・The art of the fly: Larry Offner of Green Trout Fly Shop

THE GEAR

・Outdoor survival kit: Baton Rouge stores offer what you need for the trek

・The Backpacker’s Tyler Hicks shares his must-haves for a hiking or camping trip

・Apps to get your outdoor adventure started

・Local lululemon ambassadors share the game-changing fitness apparel they’ve discovered

THE GRUB

・5 power snacks to bring on your outdoor adventures

・Go beyond s’mores with these campfire recipes—no pot or pan required